(This essay was originally published by the Newport Daily News on May 7, 2014.)

Next to Martin Luther King, Frederick Douglass was probably the greatest African-American in US history. Unlike King, Frederick Douglass—born Frederick Bailey in February 1818—was not killed by an assassin’s bullet, but rather lived until January 9, 1895.

Douglass was born a slave. His mother, Harriet Bailey, was black, while his unknown father was white, perhaps Colonel Edward Lloyd, the plantation owner, or one of Lloyd’s sons. He lived on the eastern shore of Maryland and also in Baltimore until the age of 20 when he and his future wife, Anna Murray—a free black—escaped. With a sailor’s garb and false free black seaman’s papers, Douglass and his wife in 1838 made their way through Philadelphia, New York City, and Newport to their final destination of New Bedford, Massachusetts, a town with a total population of 12,354, including 1051 blacks. Having never been to a free state, Douglass was surprised at the “wealth, refinement, enterprise, and high civilization” of the city, believing that “poverty must be the general condition of the people of the free states.” Before he left Baltimore, he had changed his name to Johnson. On the advice of his friends, he now changed his name to Douglass. Working as a free man and earning decent pay, he was “imbued with a spirit of liberty.” Within a few years, Douglass, Anna, and their three children became respectable members of the black community.

During his years in New Bedford, Douglass came to realize his tremendous gift of oratory which he soon employed in the great cause of the day—abolitionism. William Lloyd Garrison led this movement, and soon Douglass was reading his newspaper, The Liberator. Garrison’s words, ideas, and unwavering conviction helped to crystallize Douglass’ calling. This gift of oratory made its debut at the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society on August 16, 1841, on Nantucket. With his personal story of slavery and his powerful voice, he succeeded in transfixing the audience. He had found his calling, and he would be heard.

Over the course of the next two decades, Douglass made over one hundred speeches each year in the antislavery crusade leading up to the Civil War in 1861. This young man, who learned the power of words early as a slave boy studying Webster’s Spelling Bee and then later The Columbian Orator, was not only a great orator but also a great writer. He wrote for Garrison’s newspaper and other publications, including his own antislavery newspaper, The North Star, and eventually the Douglass’ Monthly. During his lifetime he also wrote three books, all autobiographical. With his violin he enjoyed playing Mozart, Haydn, and Haendel.

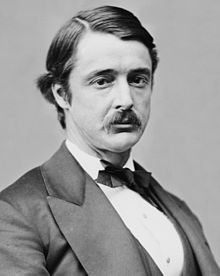

Douglass circa 1860s

(Wikipedia.com)

During the Civil War, Douglass worked tirelessly for the emancipation of slaves and for equal rights for African-Americans. In 1848 he first met the zealously antislavery John Brown and learned of his bold scheme to foment a slave insurrection and to establish a black state in the Appalachian Mountains. Douglass resisted participating in Brown’s seizure of Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859; however, he had knowledge of it and was pursued by his enemies. Douglass fled to first Canada and then Great Britain, returning the following year after the death of his daughter.

Striving to maintain as many states as possible in the Union, President Abraham Lincoln emphasized until September 1862, that the paramount goal of the war was to restore the Union and not to abolish slavery. Douglass and other abolitionists attempted to change his mind. “Sound policy … demands the instant liberation of every slave in the rebel slaves,” said Douglass. He also argued for the recruitment of blacks into the Union military forces. In January 1862, he said, “We are striking the guilty rebel with our soft, white hand, when we should be striking with the iron hand of the black man.”

After Emancipation on January 1, 1863, Douglass had his first of three meetings with President Lincoln. During the first in August 1863, Lincoln defended his policies toward blacks and hoped that Douglass saw this not as “vacillation” but as slow but steady progress in securing the rights of blacks. Douglass left the meeting jubilant over Lincoln’s gracious and respectful manner toward him.

After the Civil War he championed the vote for blacks—and women, and served as the president of the Freedman’s Bank in Washington, D.C., as the marshal of that city, and as the American minister to Haiti. These years were filled with frustrations, defeats, as well as triumphs; however, Douglass never relinquished his efforts for full racial equality in America, or—like Martin Luther King—for our country to live up to the promises in its founding documents.