(This essay was originally published abridged in the Providence Journal on August 5, 2023.)

The storied Gilded Age of American history, with its epicenter in New York City and eventually in Newport, RI, began 150 years ago. This age is at once part of the epic story of American capitalism’s astounding ability to create wealth, but also a cautionary tale of how great wealth can be squandered.

While most historians begin the age in 1870, the year 1873 is more apt. In that year Mark Twain and co-author, Charles Warner, published a novel entitled, “The Gilded Age,” in which they offer vivid portrayals of greedy industrialists and corrupt politicians in Washington, DC.

Also in that year two eventual leaders of New York City high society met: Ward McAllister, the self-made social maestro of all things that glittered, and the commanding Caroline Astor, wife of William Blackhouse Astor, Jr., the head of the Astor family, the richest in America in the mid-19th century. Looking to introduce her daughters to society, she brought her old-money wealth and prestige while McAllister brought his impeccable taste and manner. Theirs was a perfect match to dictate social custom, protocol and standing. She became the undisputed “Queen” of New York and then Newport society.

Ward McAllister

They both had been troubled by the many families who had only recently acquired wealth in the rapidly burgeoning American economy, thanks to the Industrial Revolution. These parvenus were attempting to wedge their way into high society; however, McAllister and “The Mrs. Astor” took it as their sacred duty to serve as the gatekeepers. Their mission was nothing less than to save society from the barbarians.

“The Mrs. Astor”

The preceding year, McAllister had prepared a list of 25 “Patriarchs” of high society New York. He said that these men: “had the right [by blood and wealth] to create and lead society.”

Each of these Patriarchs was charged with inviting four women and five gentlemen to the first annual Patriarchs Ball in the winter of 1873. This list eventually approached the figure of 400, a number which also served as the maximum capacity of Mrs. Astor’s ballroom in NY City.

McAllister told the press: “Why, there are only about 400 people in fashionable New York society. It you go outside that number you strike people who are not at ease in a ballroom or make other people not at ease.”

A decade later the center of New York society moved—for only the two prime summer months—to Newport, RI. In the 1850s, Ward McAllister had bought farmland on the same island as Newport, a place of magnificent natural beauty and cool summer ocean breezes. With his encouragement, the Astors bought the Beechwood mansion in 1881.

Beechwood

By the late 1880s, the Vanderbilts, the Goelets, the Belmonts, the Fishes, and others followed, seeking to escape the heat of New York City summers. They bought, built, and staffed opulent mansions, which they called “cottages,” principally on Bellevue Avenue in Newport. Fifth Avenue shops also followed and opened outlets for the season. The “summer colony” was established.

The great wealth that these families had amassed allowed them to luxuriate in a carefree summer idyll, what economist Thorstein Veblen called “conspicuous consumption,” with social calendars packed not only with teas, dinners and balls, as in New York, not only with many picnics in the beautiful venues the Newport area offered, but also with expensive hobbies.

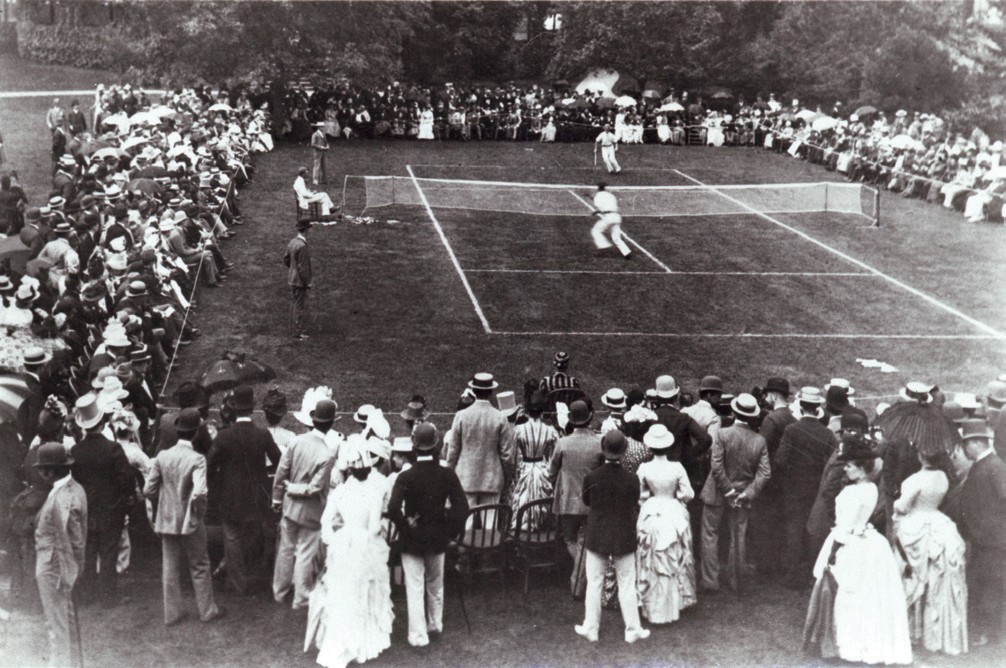

In 1880, James Gordon Bennett, publisher of the influential New York Herald, completed The Casino, described as the most lavish resort in America. Despite its name, there was no gambling; rather it offered cards, croquet, tennis, dances and concerts. The following year it hosted the first U.S. Nationals tennis tournament.

With its wonderful harbor leading to Narragansett Bay, leading to the Atlantic Ocean, Newport was a marvelous location for sailing and yachting.

In 1893, the Newport Country Club was established, hosting two years later the first U.S. (Golf) Open and the first U.S. Amateur Open.

Once trolley service allowed the masses access to Easton’s Beach, the main beach in Newport, the rich in the 1890s organized the Spouting Rock Beach Association and opened the exclusive Bailey’s Beach.

Daily in the late afternoon, after another wardrobe change for the ladies, they mounted their horse-drawn carriages and joined the daily procession down Bellevue Avenue. Ladies might bring up to 90 dresses for the summer season. Feathered hats and white gloves, three or four new pair each day, completed their ensembles.

Once “automotive machines” appeared, the rich—of course—purchased the newest and most expensive and staged races and other auto events.

William K. Vanderbilt, 1904

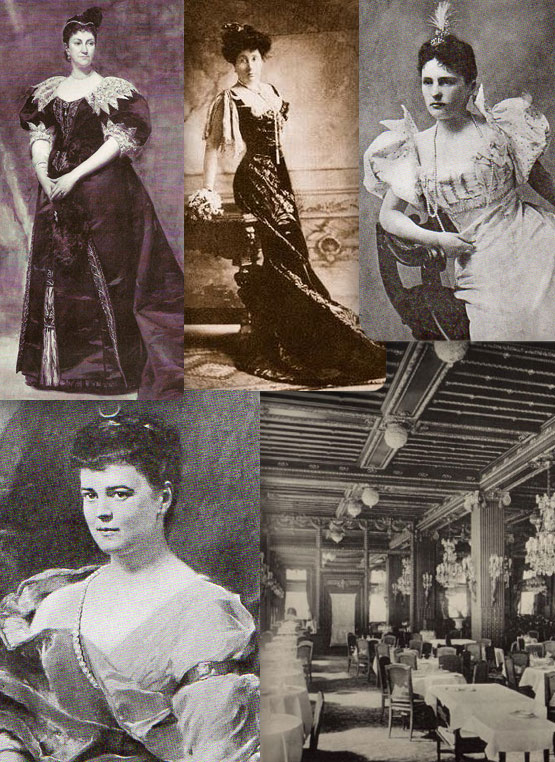

For the most part, women ran this society, their husbands busy at work during the week and joining them on weekends. The four leaders of high society included Caroline Astor, Alva Vanderbilt (who eventually married Belmont), Marion “Mamie” Fish, and Theresa “Tessie” Oelrichs. They all owned opulent mansions on Bellevue Avenue or nearby Ocean Drive.

Though not one of the influential leaders, Alice Vanderbilt and husband Cornelius II built the largest of the Newport mansions, The Breakers: 70 rooms on a twelve acre plot overlooking the ocean, thirty baths with hot and cold fresh and salt water, costing $7 million ($254 million today) to build and certainly millions more to furnish.

The fortunes these families made in railroads, real estate, shipping, coal, the China trade, and other businesses allowed them to be waited on by platoons of servants. While a skeletal staff of a dozen might suffice, many more than this might be needed to complete the staff of one of these cottages. In 1895, there were 2,287 servants working in Newport, almost 10% of the population.

Not the case with all these families, but certainly for the Vanderbilts, America’s richest family for several generations, the Gilded Age offers a cautionary tale. Vanderbilt scion Anderson Cooper writes in his book (with Katherine Howe), Vanderbilt: “This is the story of the greatest American fortune ever squandered.” And Arthur T. Vanderbilt II writes in his book, “Fortune’s Children”: “When 120 of the Commodore’s [Vanderbilt] descendants gathered at Vanderbilt University in 1973 for the first family reunion, there was not a millionaire among them.”

A retired educator, Fred Zilian (pegasusenrichment.com) gives tours of Newport and lectures on its history.