(This essay was originally published in the Newport Daily News on August 29, 2012.)

From our Declaration of Independence in 1776 to the start of the Civil War in 1861, slavery posed a fundamental contradiction to our American identity. How could the same country whose Declaration stated “all men are created equal” and which held itself on high as the exemplar of freedom allow slavery? Indeed, there were slave markets right in our nation’s capital.

Unable to resolve differences over slavery, our Founding Fathers avoided mentioning the word in our Constitution. It essentially recognized slavery as lawful by counting each slave as three-fifths a person for purposes of taxes and representation in Congress; however, it refers to them as “other persons,” or a “person held to service or labor.” Historian Barbara Fields has stated that “if there was a single event that caused the war, it was the establishment of the United States … with slavery still a part of its heritage.”

When in 1793 Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, allowing the easy removal of cotton seeds, production of cotton and consequently the demand for slaves soared.

Slavery began in Rhode Island, as with the other American colonies, in the 17th century. In 1652, the colony passed the first abolition law in colonial America; however, the law was not really enforced. In the 18th century the colony’s economy became largely dependent on the trade triangle: rum produced in the colony would be exported to Africa for slaves, these slaves would be brought to the Caribbean for molasses and sugar, these commodities would come to the colony to produce the rum.

During the 18th century, Newport and Bristol became major slave markets in the American colonies. Between 1709 and 1807, Rhode Island merchants like John Brown and George DeWolf financed nearly 1000 slave voyages to Africa and carried over 100,000 slaves to the Western Hemisphere. By 1774, slaves made up 6.3% of the colony’s population, twice as high as any other New England colony. Anti-slavery laws were passed in 1774 and 1784; however, the transatlantic slave trade continued even after the United States banned it in 1807. By the mid-19th century, many Rhode Islanders were active in the abolitionist movement, particularly Quakers in Newport and in Providence such as Moses Brown.

Straining to maintain this so-called “peculiar institution,” so vital to their economy and way of life, southerners defended slavery vehemently, feeling themselves in mortal combat with their northern oppressors. By 1840 southerners maintained that slavery was “a great moral, social, and political blessing—a blessing to the slave, and a blessing to the master.” It civilized African savages and provided them social security for life in contrast with the sordid poverty of “free” labor in the North. Some southerners such as Edward Pollard and George Bickley of Virginia even envisioned the extension of the southern version of American liberty to the Caribbean and Central America. Slavery created a far superior society to the “vulgar, contemptible” Yankees. The famous South Carolina politician John C. Calhoun summed up the southern view by maintaining that slavery was a “positive good … the most safe and stable basis for free institutions in the world.”

A slave’s life was misery. One freed slave stated: “No day ever dawns for the slave, nor is it looked for. For the slave, it is all night.” Children were sent to the fields at twelve. Slaves worked from sunrise to sunset, and on moonlight night’s they would work longer. On the auction block, slaves were naked so that buyers could see how little they had been whipped. Historian James McPherson noted that the breakup of slave families was the “largest chink in the armor” of defenders of slavery. It was this theme which author Harriet Beecher Stowe dramatized in her highly influential bestseller, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852. Slave marriage was not recognized as legal, so preachers changed the vows to “until death or distance do you part.”

(USslave.blogspot.com)

A former slave stated: “If I thought I’d ever be a slave again, I’d just take a gun and end it all right away, because you’re nothin’ but a dog.”

The greatest African-American of the 19th century, Frederick Douglass, freed man, abolitionist, writer, and orator, stated: “In thinking of America, I sometimes find myself admiring her bright blue sky, her grand old woods, her fertile fields …, but my rapture is soon checked when I remember that all is cursed with the infernal spirit of slave-holding and wrong…. I am filled with unutterable loathing.”

Essayist John J. Chapman called slavery the “sleeping serpent” that lay coiled up under the table at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. In the 1850s it awoke, and in 1861 it envenomed our country.

Follow me on Twitter: @FredZilian

Rhode Island Joins March to War

(This essay was originally published in the Newport Daily News, May 26, 2012)

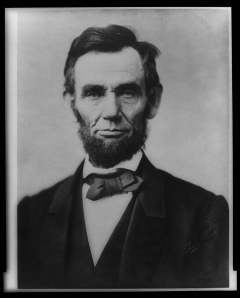

After the South’s bombardment of Fort Sumter, on April 12, 1861, President Lincoln issued a call to arms on April 15 and established Rhode Island’s quota at 780 men. Governor William Sprague called the General Assembly into special session on April 17, and both Houses quickly passed unanimously a resolution to meet the quota. Various state banks came forward and offered loans to meet the financial requirements. Finally, acts reviving the charters of the Providence Horse Guards, the Narragansett Guards, the City Guards of Providence, and the Wickford Pioneers were approved.

During the period April 18-24, Rhode Island sent its first units off to war. On April 18, the Providence Marine Corps Artillery left Providence. Following this unit were two detachments composing the First Regiment, Rhode Island Detached Militia, commanded by Colonel Ambrose E. Burnside. On April 20, the first contingent, 530 men, under the command of Burnside departed on the Steamer Empire State. These men came from the ten companies making up the regiment, six from Providence and one each from Pawtucket, Woonsocket, Westerly, and our own Newport. As the ship passed Newport Harbor, salutes were fired from the city and Fort Adams to honor the departure. The second contingent of 510 men, under the command of Colonel Joseph T. Pitman, departed Providence by steamer on April 24. As they marched to the Fox Point pier, they sang their regimental song:

“The gallant young men of Rhode Island

Are marching in haste to the wars:

Full girded for strife, they are hazarding life

In defense of our banner and stars.”

Second Detachment of the First RI Regiment departing Providence, April 24, 1861

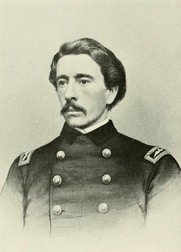

Burnside eventually became the most renowned Rhode Island Civil War hero. Born in Indiana, he graduated West Point, served in the Mexican War (1846-48), married Mary Fisher from Providence, and invented and manufactured in Bristol a breech-loading rifle. Shortly after Fort Sumter, Governor Sprague asked him to lead the First Rhode Island Regiment. He gave his name to the style whiskers which he wore.

Burnside reported to the governor that during the final marches to the nation’s capital: “Nothing whatever occurred to detract from the good reputation of the State, whose patriotism had called into active service the fine body of men whom I esteem it an honor to lead.”

On April 29, the First Detachment welcomed their fellow soldiers from the Second Detachment and escorted them to the Patent Office grounds where they had temporary quarters. That same day the entire regiment marched to the White House and was there welcomed by President Lincoln, Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, the Army Commander in Chief, Secretary of State Seward and Secretary of War Cameron.

On May 2 the entire regiment was paraded with Governor Sprague, President Lincoln, and many spectators observing. It was then marched to the Capitol where the regiment was mustered into service for the United States for a period of three months. Each soldier recited the following oath of allegiance:

“I ___________, do solemnly swear, that I will bear true allegiance to the United States of America and that I will serve honestly and faithfully against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever, and observe and obey the orders of the President of the United States, and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to the rules and regulations for the government of the armies of the United States.”

Colonel Burnside reported that “eleven hundred voices rose in one volume upon the air.”

In his first official report to Governor Sprague on May 23, Burnside closed by saying, “I cheerfully bear testimony to the general good conduct and character of the men composing this Regiment. It is with the greatest satisfaction, that I can commend them to the favor and generosity of the people of the State whose honor they are engaged in upholding, and whose good name they are determined to maintain.”

It would be this good name that would be put to the test when the First Rhode Island Regiment took part in its first combat at the First Battle of Bull Run in July, 1861.

For more information, please visit the state’s Civil War Sesquicentennial Commemoration Commission website: www.rhodeislandcivilwar150.org.