(This essay was originally published as “Recounting the Battle of Rhode Island,” by the Newport Daily News on August 29, 2018.)

(Note: This is the second of two essays, celebrating the 240th anniversary of the battle.)

The American victory in the Battle of Saratoga (NY) in October, 1777, had a strategic impact on the Revolutionary War. It convinced the French to ally with us. In February, 1778, France signed a treaty of commerce and friendship and also a treaty of alliance with the fledgling United States. Great Britain now faced a much different threat. The US was hopeful and emboldened.

On July 29, the French fleet arrived off Pt. Judith. Under the command of Charles Henri Théodat, Comte d’Estaing, it consisted of 16 ships, with 12 ships of the line and about 4,000 army troops. The British naval forces were clearly overmatched so they took defensive measures. They withdrew their forces spread throughout the island to defensive positions near and in Newport. They also scuttled about 10 ships to prevent them from falling into French hands.

On August 8, d’Estaing moved the bulk of his fleet into Newport harbor. However, the next day British Admiral Howe and his fleet, a relief force, were spotted off Pt. Judith. On August 10, the fleets were maneuvering for position in the Atlantic south of the bay; however, Mother Nature stepped in. A tremendous hurricane arrived and raged for two days, disabling both fleets.

During this same time, the American forces, led by Maj Gen John Sullivan, had launched an offensive from Tiverton across Howland’s Ferry and landed unopposed in Portsmouth. They quickly occupied the fortifications which the British had evacuated, most prominently, Fort Butts, where the Portsmouth town wind turbine now stands. Gen Sullivan decided on a siege of Newport to try to strangle the British until the French fleet returned to the bay. American forces advanced in the east as far as the high ground east of Valley Rd. (Honeyman’s Hill), in the west as far as the high ground north of Miantonomi Ave.

Worried about the British relief force enroute, Adm d’Estaing informed Gen Sullivan that he was taking his fleet to Boston for repairs. The Americans were stunned and angry; Gen. Sullivan was indignant.

Thus began the unraveling of the allied offensive operation. To make matters worse, the terms of enlistment for several of the militia units were expiring. They wanted to get back to their farms and families. Lastly, sickness, especially dysentery, began to take its toll. On August 24, the siege ended and American forces began a retreat. British commander, Gen Robert Pigot, sensed an opportunity.

By August 29, the American force had declined to about 7,800 men; British-Hessian forces totaled about 6,000 soldiers and marines. The enemy line ran from Quaker Hill to Turkey Hill to Almy Hill. The forces on the western flank were mostly German regiments and they faced, among other units, the 1st RI Regiment, called the “Black Regiment” because of its many black and mixed-race soldiers.

Commanded on this day by Maj Samuel Ward, the regiment was situated behind a “thicket in the valley,” which gave them a strong defensive position. They also used the stone walls in this area as defensive positions from which to fire on the advancing troops. The Regiment had the primary responsibility for holding an important fortification on Durfee’s Hill, now called Lehigh Hill.

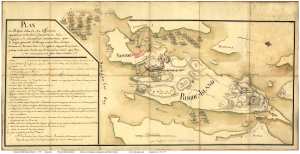

Disposition of British, French, and American Forces, Aquidneck Island, French Map, August 1778

Disposition of British, French, and American Forces, Aquidneck Island, French Map, August 1778

(Library of Congress)

Three full assaults by Hessian forces failed to break the line. All the while Hessian cannon were firing on them from Turkey Hill. In his diary, one of the Hessian commanders, Captain Friedrich von der Malsburg, noted that during these assaults, “they found large bodies of troops behind the works and at its sides, chiefly wild looking men in their shirt sleeves, and among them many Negroes.”

In seven hours of combat that day, the American line held. This allowed for the successful retreat and evacuation of General Sullivan’s Army to Tiverton across the Sakonnet River. Regarding casualties, Gen Pigot’s official report stated combined British, Hessian, Loyalist casualties of 260 with 38 killed. Gen Sullivan reported casualties of 211, with 30 killed.

Tactically, the battle is considered a draw. Neither commander wanted a full-scale battle. British Gen Pigot was happy to get the American force off the island. He had no desire to risk his military force or Newport for a chance to gain a decisive victory. Gen Sullivan was happy to get his force off the island before the British reinforcements arrived.

Strategically, most historians would call the entire campaign a win for the British. They were not captured or pushed off the island. They remained another 14 months until they decided to end the occupation in October 1779.

Nonetheless, this was the first time that American and French forces had planned an allied military operation, one they would have executed, but for the hurricane. Finally, it was the largest battle of the war in New England and the last significant battle in the northern theater, one which unfortunately has never made the US history texts.

A monument to the Black Regiment now stands in Patriots’ Park, Portsmouth, and is dedicated to the “first black slaves and freemen who fought in the Battle of Rhode Island as members of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment.”

Fred Zilian (zilianblog.com; Twitter: @Fred Zilian) teaches history and politics at Salve Regina University, writes for The Hill and the History News Network, and is a monthly columnist.

Sources:

“The Battle of Rhode Island.” Rhode Island Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. http://rhodeislandsar.org/battleri.htm. Accessed April 14, 2019.

Crane, Elaine Foreman. A Dependent People, Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era. New York: Fordham University Press, 1985.

Geake, Robert A. From Slaves to Soldiers, The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2016.

Greene, Lorenzo. “Some Observations on the Black Regiment of Rhode Island in the American Revolution”, The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Apr., 1952), pp. 142-172

Johnson, Donald. “Occupied Newport: A Revolutionary City under British Rule”, Newport History, Vol 84, Summer 2015.

MacKenzie, Frederick. The Diary of Frederick MacKenzie, Giving a Daily Narrative of His Military Service as an Officer of the Regiment of Royal Welch Fusiliers During the Years 1775-1781 in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York. Vol I & II. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930.

McBurney, Christian M. The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2011.

Schroder, Walter K. The Hessian Occupation Of Newport And Rhode Island,1776-1779. Westminister, MD: Heritage Books, 2005.

Stensrud, Rockwell. Newport, A Lively Experiment, 1639-1969. London: D Giles, 2015.

Youngken, Richard C. African Americans in Newport, An Introduction to the Heritage of African Americans in Newport, Rhode Island, 1700-1945. Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, 1998.

Great essay!